The Hindu publicaba el mes pasado un artículo sobre la trayectoria de la interpretación bilateral en la India. Según la revista, durante años muchos ciudadanos de la India o de países africanos se han visto desfavorecidos en las conferencias internacionales debido a las condiciones que fija Naciones Unidas sobre las lenguas de trabajo de los intérpretes, ya que la lengua materna del intérprete tiene que ser idioma de Naciones Unidas. Sin embargo, los intérpretes indios han echado por tierra esas restricciones con sus brillantes intervenciones en las conversaciones bilaterales entre líderes indios y dignatarios extranjeros.

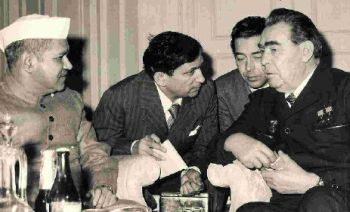

Foto cortesía de Shrikant Oak

Gracias a su empeño, intérpretes como Madhu Vinayak Oak y Santosh Kumar Ganguly han conseguido demostrar la valía de los intérpretes indios, que –de momento– no están representados en la AIIC.

High speed drama

[S. Rangarajan, The Hindu, 20 September 2009]Bilingual interpretation is a highly skilful and a very demanding profession. The era of interpretation started in 1919 after the First World War at the Paris Peace Conference. The American President, Woodrow Wilson and the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George challenged the monopoly of French as the international diplomatic language and successfully campaigned for the adoption of both French and English as the official languages in the League of Nations, the Permanent Court of International Justice and the International Labour Office (ILO) thereby sparking the demand for conference interpretation services.

Initially it was an age of consecutive interpretation when the speaker and the interpreter were seen side by side on the same podium. The two spoke in tandem; the interpreter rendering an oral translation of fragments of the original speech. The whole process was a long and time-consuming affair until 1925 when Edward Filene suggested a simultaneous interpretation system at the League of Nations. The improvements and advances in the audio communication services enabled the adoption of simultaneous interpretation when the interpreter finished seconds after the original speech.

Over the years Indians and Africans are unfortunately at a disadvantage in international conferences because of the restriction that one of the languages at the United Nations must be the mother tongue of the interpreter. But Indian interpreters have knocked out this restriction by their brilliant performances in bilateral talks of Indian leaders with foreign dignitaries.

In 1954, a junior official in the Embassy of India in Beijing gave bilateral and bilingual interpretation a dramatic push. V.V. Paranjpe, a Sanskrit scholar who had learnt Chinese during the World War II, was in the right place at the right time. Prime Minister Nehru was visiting China and, in the absence of a Chinese Ministry interpreter at a particular moment, Paranjpe filled in at short notice. Amazed by his performance, Zhou en lai is reported to have told the Indian Prime Minister that the interpreter’s Mandarin Chinese was perfect. Paranjpe’s star began rising in the diplomatic firmament and he rose to become India’s Ambassador to South Korea in Seoul, a vantage point to observe political developments in the region.

Nehru noted that the interpreter’s service in the Ministry of External Affairs must be developed and improved, but it took nearly three decades of uphill battle for this task to be achieved. Madhu Vinayak Oak and Santosh Kumar Ganguly successfully proved that Indian interpreters were equal, if not superior to any in the profession from any other country. Both worked in the Indian Embassy in Moscow.

Both had learnt Russian in New Delhi in the 1950s and early 1960s when facilities for learning foreign languages were very limited if not negligible. Madhu, as Oak was affectionately called, broke the barrier that only Russians could interpret for both Indian and Russian leaders during bilateral talks. He managed to attract Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s attention during her visit to Moscow in the late 1960s and went on to become a permanent feature of Mrs. Gandhi’s talks with Mr. Kosygin and Mr. Brezhnev.

During Narasimha Rao’s tenure as Foreign Minister, Santosh carried the battle forward successfully to gain interpreters due recognition in the diplomatic service, refuting the bureaucratic belief that interpreters were only messengers. By becoming India’s first Consul-General in St. Petersburg, Ganguly established that the interpreter’s role implied as much analysis and observation as that of the diplomats.

Around the same time in Paris, Pushpa Das (called Pouchappa Das by the French) was making a name for himself. A native of Pondicherry, Pushpa Das could easily claim French as his mother tongue, though the French would not accept this as easily.

The facilities for learning Arabic and the demand for Arabic interpretation are far more in India than for other foreign languages. The Ministry of External Affairs has a large cadre of Arabic interpreters, some passing out of the prestigious Al Azhar University of Cairo.

Bilingual interpretation can sometimes be a tricky affair. To highlight the need for resumption of diplomatic negotiations with Russia in several fields, Hillary Clinton, U.S. Secretary of State, presented a button with “peregruzit” inscribed on it to the Russian Foreign Minister, Lavrov. The Americans thought “peregruzit” meant “to reboot” or restart; whereas, unfortunately, the real meaning was “to overload” or “to overstrain”, as Lavrov pointed out. Both Clinton and Lavrov laughed over the gaffe and “peregruzit” has come to be accepted to mean restart giving an unexpected push to U.S.-Russian talks. Fortunately so far the Indian interpreters are not known for such diplomatic and linguistic faux pas.